Forming Conflict Identities:

The Role of Subgroup Leaders in Combatant Socialization

[My dissertation is available to download here]

What explains the variation in socialization outcomes in armed organizations? Why do some combatants adopt the intended norms of their organization while others resist them? The socialization processes of armed organizations profoundly shape the behaviors and attitudes of combatants and directly influence their repertoires of violence. Recent scholarship on the internal dynamics of armed organizations has advanced our understanding of within group factors that shape combatant preferences, but there are still significant theoretical and empirical gaps on combatant socialization.

My doctoral research presents and tests a framework that socialization is driven by subgroups—the smaller social units within armed organizations that form the informal structure and environment of combatants. Specifically, subgroup leaders—the junior and mid-level commanders of an organization—regulate the socialization processes of combatants by reinforcing (aligned leaders) or undermining (divergent leaders) the official norms of the organization. Subgroup leaders occupy a unique position of authority within both the formal and informal social networks of an armed organization that enables them to control the normative environment of combatants.

I test this expectation using a mixed-method nested research design that leverages archival data from the American (1944-1945) and British (1946-1948) re-education programs for German prisoners of war (POWs) which sought to ‘democratize’ them. These unique cases of combatant socialization provide exceptional data on the changing attitudes and subgroup leadership of German combatants. First, I conduct a controlled comparative case study of German POW camps in the UK, where British officials installed pro-democratic POWs into subgroup leadership positions in select camps. Second, I conduct the first systematic analysis on the British re-education program for German POWs using a novel dataset constructed from administrative reports to compare the variation in socialization processes and outcomes based on the subgroup leadership type of each camp. Third, I present a cross-case comparative study of the British and American re-education programs, which differed in their policies towards German subgroup leaders. Together, these analyses lend support for the argument that subgroup leaders shape socialization outcomes.

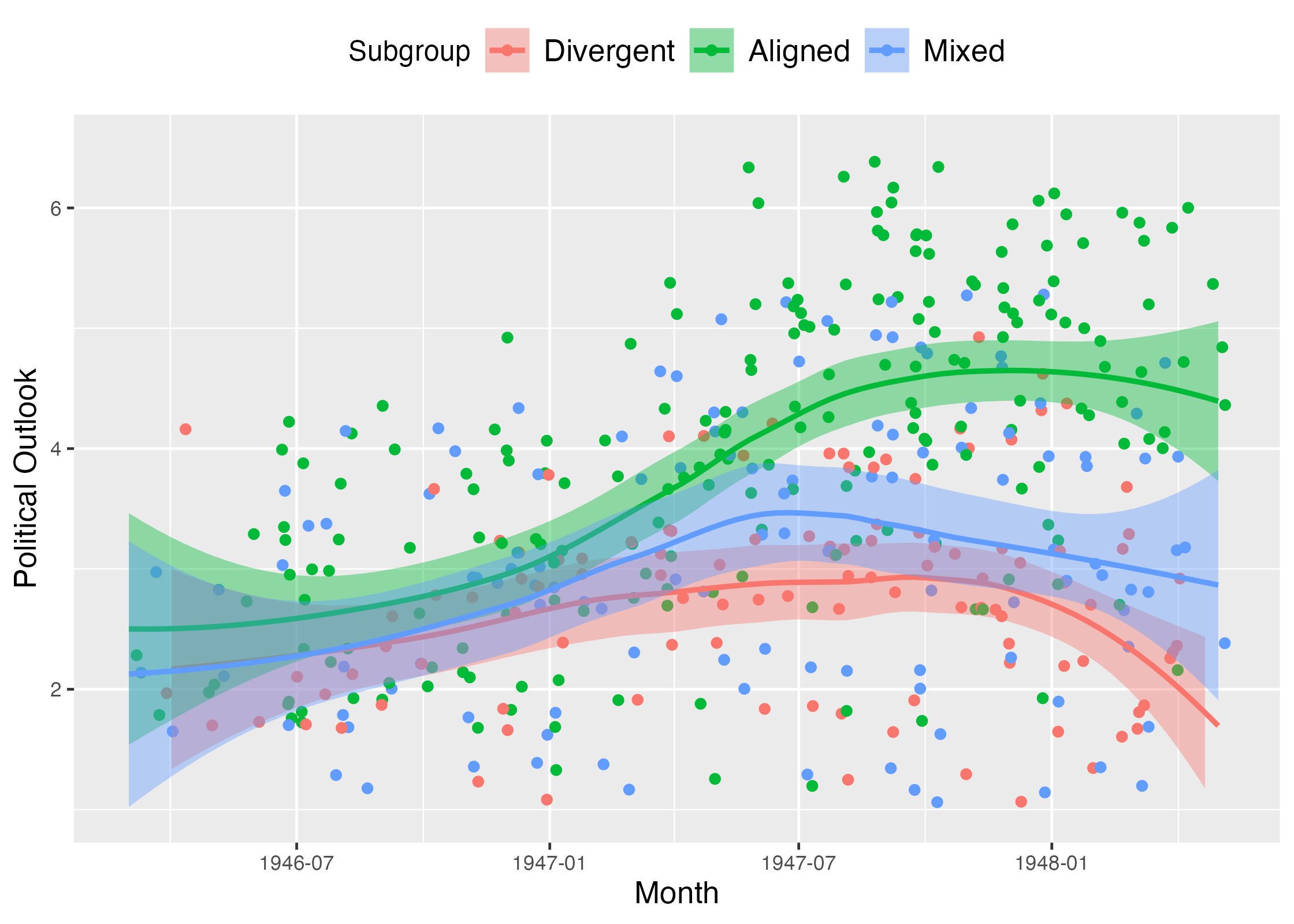

Here I preview my findings from the large-N empirical chapter on the British re-education program. From 1946 to 1948, British officials implemented a comprehensive ‘democratization’ program for the massive population of German POWs in the UK, which at its peak in September 1946, numbered 402,177 POWs spread across approximately 220 camps (“Progress Reports,” FO 939/419, TNA; “Strength Lists,” FO 939/245, TNA). To track the progress of re-education, British officials regularly visited POW camps to compile reports on the overall state of re-education (see example report collected from the UK National Archives at the bottom of this page). These reports provide quantitative and qualitative data for tracking the shifting attitudes of German POWs and detail information on the German leadership of the camps. In select camps, British officials significantly altered the subgroup leadership of POWs by replacing overtly Nazi or apolitical leaders with pro-democratic leaders. Leveraging this variation in subgroup leadership types, I compare the socialization outcomes of POW camps with pro-re-education subgroup leaders. The analysis tracks the socialization trajectories of 64 different camps using monthly reports (n = 489).

Note: Political Outlook measures the socialization trajectories and outcomes of each camp, tracking their cumulative periods of improvement or decline in democratic norms.

As the figure above illustrates, German combatants with aligned, pro-re-education, subgroup leaders were more likely to develop democratic and pro-British norms while combatants with divergent, apolitical or Nazi leaders were less likely to adopt the expected norms of the re-education program. In most POW camps, the support or opposition of German camp leaders to re-education significantly shaped the social environment of rank-and-file POWs and how they interpreted democratic norms and their overall levels of participation in re-education. These patterns are further reinforced by a multitude of additional quantitative and qualitative evidence presented in my dissertation which shows the mechanisms and timing of subgroup leader influence on combatant preferences.